Table of ContentsShow

At some point in their lives, everyone will be exposed to botanical plant names. People generally know various trees, shrubs, and flowers by their common names, but invariably they will come across the Latin names for many plants, and invariably people will find them confusing at first. Most homeowners and even a good number of gardeners don’t quite get the idea behind the botanical lingo and find it even more difficult to use as a means of identifying their plants.

And yet, for all the grief that botanical names cause, they serve a critical purpose in the world of gardening and landscaping. They solve the problem that originates with the common names for plants, which are fraught with discrepancies and far more confusion, particularly when it comes to uniquely identifying a particular plant.

The Trouble With Common Plant Names

For one thing, common names are not universal. Many regions and locales have their own colloquial names for certain plants that mean nothing in another part of the country. For example, American hornbeam (the “accepted” common name for Carpinus caroliniana) is alternatively known as blue beech, ironwood, and musclewood, depending on where you find it growing. In some areas hostas are known as plantain lilies, astlibes are called false spirea, caragana is known as peashrub, arborvitae is white cedar, and potentilla is the cinquefoil. There is simply no “universal standard” for these names.

Which leads to the second and more insidious problem; many rather different plants often share the same common name. In fact, plants from completely different genera can have the same name! Ironwood alternatively refers toCarpinus carolinianaandOstrya virginiana, false spirea is the common name for bothAstilbeandSorbaria, and there are 3 or more coneflowers. How is one to know which plant is actually meant?

And the icing on the cake is that some plants are just incorrectly named by any logical measure. Poison oak isn’t an oak at all, it’s a member of the Sumac family, blue beech isn’t even a true beech, and some of the false spireas aren’t remotely related to spireas while others actually are!

Clearly, common names are not the ideal way to identify plants. A more distinctive, universal, and unique system was required to pin down a name that would explicitly refer to one and only one kind of plant. That system of classification was provided by the great botanist Carl Linnaeus of Sweden back in the late 1700s, and it is still in use today.

The Universal Plant Classification System

Here’s how the botanical naming convention works. It’s a hierarchical system, kind of like a pyramid, with the broadest classification on top, effectively all of life. This then splits down into successive tiers through the plant kingdom and then into specific groupings of plants, until you get down to the bottom tier which uniquely defines one specific plant. Any individual plant can be traced back up the system, tying it back into the rest of life on Earth as we know it.

Here is the basic structure for the classification and naming of plants;

| Kingdom (plants) | ||||||||

| Division | ||||||||

| Class | ||||||||

| Order | ||||||||

| Family | ||||||||

| Genus | ||||||||

| Species | ||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||

| Cultivar/Variety | ||||||||

Each of these tiers represents a grouping of plants that share similar characteristics. The top classifications have the loosest or broadest associations, while those at the bottom have more specific and readily identifiable commonalities. Starting with the family, here is the basic logic behind each of the groupings;

Family

Defined as plants sharing commonalities of general appearance or characteristics; usually, these are grouped according to similarities in fundamental reproductive characteristics (i.e. flowers, fruit). The formal family name always ends in “aceae”; for example, Rosaceaeis the Rose family.

Genus

These are defined as clusters of plants within a family that have strongly associated characteristics. Here the common characteristics are expanded to include leaves, buds, roots, and branches or stems, and are more visible or distinguishing. Roughly speaking, the genus is what we would associate with a particular “type” of the plant; for example, Aceris the maples,Rosa is the roses, andThymusis the various kinds of thyme.

Species

This is the most important grouping of plants; it answers the question “What kind of oak” or “What kind of iris”. This grouping is defined as plants sharing a commonality of any or all essential features used for the purposes of plant identification. In other words, you should be able to identify the species of a particular plant by a visual examination of any one plant in the species. The characteristics can be anything uniquely notable, such as distinguishing colors, shapes, sizes, habits, etc. However, while they are clearly similar, the plants are not genetically identical, and plants in this grouping level almost always reproduce sexually (i.e. from seed).

Subspecies

Sometimes, plants can be grouped one level further within a species; these are usually associated with a single common trait that sets them apart from the species. Often it describes a stable variant, mutation, or anomaly that is carried to the offspring, or a local strain with a distinctive geographical association. For example, “inermis” means “unarmed” in Latin, and the subspecies var. inermis” refers to the lack of thorns in a strain as a single distinguishing trait. You’ll find thornless subspecies in the genera Gleditsia(honeylocust) andCrataegus(hawthorn), which are normally thorned.

Cultivar or Variety

These two terms are synonymous (cultivar being an abbreviation of the phrase “cultivated variety”) and define the strongest possible relationship between two or more plants. Cultivars are almost always genetically identical to one another, and as such are usually asexually (vegetatively) propagated or cloned. However, in a few cases, they can be seed-propagated as well if traits are vigorously maintained across generations.

Naming Convention Syntax

The plant naming convention is based on a specific sequence of terms that together uniquely identify a particular plant. The system uses Latin terms, not as a means to confuse people, but as a means to clearly distinguish botanical names from common names. In practice, however, many of the Latin names, particularly the “genus”, have become the common name as well; potentilla, caragana, hosta, iris, and sedum are examples of this.

In the conventional use of the botanical naming system for plants, it’s common to start with the “genus” and work downwards. For the most part, the genus is the highest level necessary to uniquely identify plants, although you’ll still often hear of plant families, which is the grouping order above. For most species of plants, the botanical name is comprised of two terms; the genus followed by the species. Both terms are always in italics, with the first letter of the genus always capitalized and the species always in lowercase. So, Quercus macrocarpais the proper botanical name for the bur oak species.

Technically, a third term should always be included, the “author citation”, which refers to the name of the botanical expert who formally developed and documented the name of the species. However, in common parlance, the author citation term is usually omitted.

When the plant is a subspecies, a third term is added to the botanical name, prefixed by the term “var.”. A good example of this is in the Japanese barberries, where the purple-leaf varieties will come true to seed. These are properly identified as Berberis thunbergii var. atropurpurea; “Berberis” is the genus for barberry, “thunbergii” is the term uniquely identifying the Japanese species (named for its “discoverer” the botanist Thunberg), and the variety term “atropurpurea” means “purple” for the color of the leaves.

Naming Convention for Cultivars

Then we come to the most important part of the classification from the perspective of gardening and home landscaping, the naming convention for varieties and cultivars. These are defined as plants with uniquely distinguishing traits that clearly set them apart from the species, and which are usually selected by plant developers to be asexually (vegetatively) propagated for commercial distribution to the public. Many of the trees and shrubs and almost all of the perennials and annuals you’ll find at the garden center are cultivars.

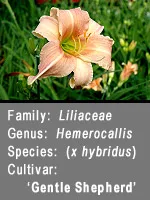

In the botanical naming convention, the cultivar term is added as a suffix following the genus and species terms. The cultivar name is framed by single or double quotes, in regular type, and with the first letters of each word capitalized. So, Russian mountain ash, a cultivar of European mountain ash (Sorbus aucuparia), is correctly identified asSorbus aucuparia ‘Rossica’, and Red Beauty yarrow is Achillea millefolium ‘Red Beauty’.

The actual terms used for cultivars are an interesting story in themselves. Back in the “old days”, prior to the mass propagation and commercialization of plants to the buying public, most varieties were identified and named according to the characteristic(s) that distinguished them from the species. In keeping with the convention, Latin terms were used as the descriptors. So, if the species had pink flowers but the particular cultivar had white flowers instead, it would be called ‘Alba’, which is the Latin word for “white”. If the typical species had red fruit but the cultivar had yellow fruit, it would be called ‘Xanthocarpum’, which literally means “yellow fruit”.

Of late, however, more and more cultivars have been named with attractive or marketing-friendly names. The wonderfully variegated Rose Glow barberry is denoted asBerberis thunbergii ‘Rose Glow’, and Royal Star magnolia is Magnolia stellata ‘Royal Star’.

As a word of note, when a cultivar is selected from a subspecies, you’ll often see the subspecies term omitted; this appears to be acceptable either way. So, Imperial honeylocust, which is a selection of the thornless honeylocust subspecies (Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis) can be written as either Gleditsia triacanthos ‘Imperial’ or Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis ‘Imperial’. In the interests of brevity, we here have opted to go with the shorter names, but they mean the same thing.

Naming Convention for Hybrids

When plants reproduce sexually, that is with a combination of male and female chromosomes, they usually cross-pollinate within their own species. Hybrids are seed-produced offspring where the two parents are not from the same species. This can occur naturally, where for example red and silver maple can hybridize in the wild, but more often are a result of intentional crosses made by plant developers. Most hybrids are not stable, meaning that the seedlings produced by the hybrid plants themselves will revert back to one of the parents rather than perpetuating the desirable traits of the hybrid, although this is not a hard and fast rule. There’s a complex genetic theory underlying this whole deal that goes well beyond the scope of this explanation!

When it comes to their classification, there are two types of hybrids; those between two different species of the same genus (called “interspecific” hybrids), and those between species from different genera (known as “intergeneric” hybrids). Interspecific hybrids are properly identified by simply omitting the species term. For example, Graham Thomas is an interspecific rose hybrid developed by famed rose breeder David Austin; this is correctly identified as Rosa ‘Graham Thomas’. Sometimes you’ll see it written as Rosa x ‘Graham Thomas’, where the “x” signifies a hybrid, but this is not technically correct.

However, you’ll often come across a grouping of hybrids, for example, multiple varieties that have resulted between the cross of the same two different species. These are often given a separate distinguishing term used in place of the species term but with an “x” in front. This term is known as the “grex”, and you’ll come across it surprisingly often at the garden center.

Most of the common border forsythias are hybrids. One common cross is betweenForsythia viridissimaandForsythia suspensa; this group has been given the grex nameFortyshia x intermedia, which includes most of the common cultivars such as Lynwood Gold, Spectabilis, and Beatrix Farrand. The hardiest evergreen hollies, the Meserve group, are known as Ilex x meserveae, named for the late Mrs. Meserve of New York, and are crosses betweenIlex aquifoliumandIlex rugosa. Blue Girl is a popular variety, and it is identified asIlex x meserveae “Blue Girl”.

Intergeneric hybrids are far less common, simply because different genera are far more distantly related than different species, and are more likely to be incompatible when it comes to pollination. These are properly identified by an “x” term in front of the genus in the botanical name. For example, there is a most unusual cross between mountain ash (Sorbus) and chokeberry (Aronia, both members of theRosaceaefamily); the botanical name is written asx Sorbaronia, where the term “Sorbaronia” is simply a contraction of the two generic names. Again, because this is a hybrid, the species term is always omitted.

Then It Gets Messy

If the above system were truly universal and had no major exceptions, it would work quite well. Unfortunately, a number of anomalies and variations have appeared, which only serve to complicate the whole deal.

For a “universal” naming system, there are sure some disagreements among the “experts” as to what name is correct, and who belongs where. There is tremendous disagreement as to whether the hydrangeas belong in their own family Hydrangeaceaeor the saxifrage familySaxifragaceae. The once whole genusPolygonumhas been totally fragmented and renamed into various genera such asFallopiaandPersicaria. The familiarCimicifuga(bugbane or snakeroot) was reclassified asActaea. Then came the fiasco of breaking up the once definitive Chrysanthemumgroup, splitting intoLeucanthemum,Dendranthemum,Nipponanthemum,andTanacetum.

While the motivations of the academics who (mis)manage these naming conventions are honorable, they create mass confusion and disruption for gardeners and the horticultural industry alike. In fact, the changing of the name of the genus of the common garden mums toDendranthemumcreated such an outcry among gardeners that they had to revert the generic classification ofDendranthemumback toChrysanthemum. It takes a lot to outrage gardeners, but they managed!

Then there are all kinds of spelling mistakes. For one thing, Latin is a gender-based language, meaning that descriptive terms and names must have their endings changed to match the gender of the genus. “Aurea” is the Latin adjective for “golden”, but it must match the gender of the genus. Since the generic Latin term for barberry is “Berberis” which is of the feminine gender, the golden barberry is correctly Berberis thunbergii ‘Aurea’. Since the generic Latin term for wayfaring tree is “Viburnum” which is masculine, the golden wayfaring tree is Viburnum lantana ‘Aureum’. Technically, that means you have to know a little about how Latin works to get the endings right!

Then there’s the absolute nightmare caused by plant patents and marketing trade names. Not only do I find this extremely difficult to explain myself, but I find the whole thing highly offensive and unnecessarily confusing to gardeners. It’s a construction of modern-day business and law that Linnaeus’ system couldn’t have anticipated; it’s what happens when the legal world of today meets the innocent academic world of centuries past, confounding a system that has worked so well.

Here’s the root of the problem as best as I can fathom it. It has to do with either registered plant names (i.e. a plant patent) or trademarked plant names. If a name is trademarked, it is afforded certain rights, and technically (actually legally) it can’t be used in the botanical name because the person who trademarked the name owns and has the sole right to that name. And yet, ironically it’s the same name that the plant will be marketed under to the general public!

So to get around this legal problem, the registering plant developers create a “nonsense” cultivar name that uniquely identifies the cultivar and which can be universally used under the law in the botanical name by anyone, not just those licensed to grow and propagate the plant. So, the popular Blue Muffin viburnum can’t correctly be identified as Viburnum dentatum ‘Blue Muffin’, which would be in keeping with the convention defined above; it has a proper syntax of Viburnum dentatum Blue Muffin (‘Christom’), where the name “Christom” is some artificial creation.

Unfortunately, this can be extremely confusing to the average gardener, since the plant is marketed and sold under the trademarked name “Blue Muffin”. If the gardener wants to use the botanical name to uniquely identify the plant, as the system was intended, they have to look for a Viburnum dentatum ‘Christom’. How on earth are they supposed to know this? It just tends to degrade into a lot of legal hoohah, which is why the policy is to simply accept the trademarked name as the proper botanical cultivar name. On the Landscape Plant Search, this is a Viburnum dentatum ‘Blue Muffin’, as one might expect.

I mean, really!